Mors Voluntaria: A Roman Death in August

by Brook Allen

It must have been a miserably hot day in August of 30 BC, when Marc Antony galloped his horse back into Alexandria, Egypt, defeated and with no hope left. His attempts to defeat his rival Octavian at sea had failed miserably at the Battle of Actium one year before. Since then, he’d won only a single skirmish against the enemy’s advance guard just outside the city, but his other efforts had been futile. Now, he had only one option open to him, and most people are aware of how his story ended.

.jpg) |

| Intaglio ring depicting the head of Marcus Antonius |

But why did Antony choose suicide? He and Cleopatra had had time to escape south into Upper Egypt or elsewhere. In fact, he had spent the past year in Alexandria. What happened during that period of time that led to this final course of action?

After Actium, and since Antony’s defeat had been at sea, he still had a land army under the command of his friend and trusted supporter, Publius Canidius. Unfortunately, things melted down more quickly than expected, with entire legions deserting Antony’s cause. Those under Canidius’s command chose Octavian, and Canidius barely made it to Antony alive to report the news. Still, Antony didn’t give up, hoping to wrest command back from one of Octavian’s commanders west of Egypt in Africa in a remote stronghold called Paraetonium. He sailed straight there, sending Cleopatra on to Alexandria. However, Antony was further humiliated, for Octavian’s troops sounded trumpets each time he attempted to persuasively speak to them.

At this point, he began to face reality and fell into deep depression. A toughened soldier and heavy drinker, Antony tried to escape into several months of drunkenness and melancholia, completely isolating himself in a small structure away from Cleopatra’s Antirhodos Palace. He named this private place his Timoneum. There, he lived away from mankind as a sort of misanthrope, styling himself after Timon of Athens. Incidentally, the location and underwater remains of the Timoneum were located through Frank Goddio’s underwater archaeological excavations in Alexandria, back in the 1990’s. We can safely assume that it was there where he first wrestled with serious thoughts of suicide.

After recently delving into the Oxford Classical Dictionary, I discovered (to my utter surprise!) that during Antony’s lifetime, no singular term for “suicide” existed in Latin Instead, it was more likely a two-word phrase: mors voluntaria—voluntary death. Here, we must remember in our age that the mindset of “sanctity of life” was primarily of Judeo-Christian origin—something Antony wouldn’t have known. Even in the ancient world, attitudes toward suicide were different than those of our present age. Instead of being aghast that so-and-so took their own life, ancients reserved judgement based upon motive, manner, and method. The OCD (Hornblower & Spawforth, 1996) states that:

“When arising from shame and dishonor, suicide was regarded as appropriate; self-sacrifice was admired; impulsive suicide was less esteemed than a calculated, rational act; death by jumping from a height (drowning), or by hanging was despised and regarded as fit only for women, slaves, or the lower classes, apparently because it was disfiguring; death by weapons was regarded as more respectable, even heroic.”

Romans themselves considered their world militant and soldierly—it was usually courage and greatness on a battlefield awarding imperium. Therefore, if a losing general or politician failed, experienced disgrace, or wished to send a powerful statement; stabbing oneself—the proverbial “falling on one’s sword”, was the accepted method. Sometimes, another man would even aid in the suicide by holding the weapon steady. Both Gaius Cassius and Marcus Brutus, Caesar’s notorious assassins, chose suicide by sword after their defeat. Julius Caesar even records military units committing suicide together during his Gallic Wars, knowing that their cause lost. One excellent example of a politician choosing suicide over Caesar’s pardon during the end of the civil war with Pompeius was Marcus Porcius Cato’s notoriously bloody suicide. After his death, not only was it acceptable, but he was hailed by optimates in the Senate as being a hero/martyr.

Antony and Cleopatra chose to wait until the very end for their fates. They shared three children between them, and both Cleopatra’s son by Caesar and Antony’s oldest boy and heir were in Alexandria with them. Cleopatra tried to organize an escape route over the desert to sail to southeast to India. Whether Antony was a part of this scheme is unknown. However, several eastern rulers who had already made good with Octavian foiled it, burning the ships Cleopatra was having hauled overland and slaughtering the armed force escorting it. Both Antony and Cleopatra tried making their own peace with Octavian. Antony promised to retire to private life in exile. Both his attempt and that of the Queen were refused. So on that hot August day in 30 BC, Antony knew his time was up.

Initially, as many Romans before him had done, he chose to have someone help him, but Eros—the chosen servant—was either too frightened or loyal to live to tell the tale, and killed himself instead of Antony. Now alone, and possibly unknowing of Cleopatra’s whereabouts, he attempted suicide with his gladius in the Roman manner. We can assume that meant by propping his weapon on the floor or against a wall or piece of furniture and slamming his full weight against it. For some lucky men using this terribly awkward method, it meant instant escape. Not for Antony.

Writhing in pain, he was still alive when he was finally discovered by one of Cleopatra’s staff and taken to her. By that time, she’d imprisoned herself inside her tomb which had a permanently locking mechanism on the main door. Unable to enter, Antony was somehow hauled up by ropes; assumedly an excruciating process in his condition.

It is said he died in Cleopatra’s arms, but the fact remains that Antony, like many Romans before and after his death, chose mors voluntaria as a way to preserve his honor, dignitas (a big-deal for Romans), and to bring closure to his life without capture. He achieved that, as well as one of the most romantic and adventuresome lives in all of Roman history.

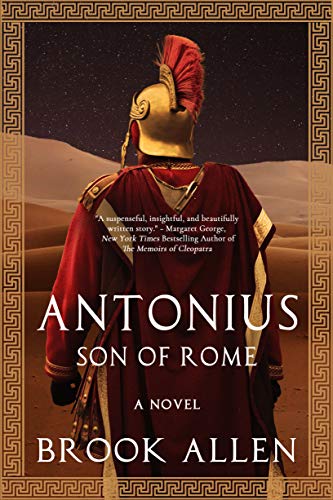

"A SUSPENSEFUL, INSIGHTFUL, AND BEAUTIFULLY WRITTEN STORY"

~ Margaret George, New York Times Bestselling Author of The Memoirs of Cleopatra

1st Place Winner in the 2020 CIBA CHAUCER DIVISION, 2020

INDIE B.R.A.G. MEDALLION AWARD FOR EXCELLENCE RECIPIENT

WINNER of the Coffee Pot Book Club BOOK OF THE YEAR AWARD, 2019

Silver Medal recipient in the Readers’ Favorite Book Reviewers Awards, 2020

"A THOROUGHLY ENGAGING STORY...HARD TO PUT DOWN."

~ Griff Hosker, Author of LORD EDWARD'S ARCHER

After young Marcus Antonius’s father dies in disgrace, he yearns to restore his family’s honor during the final days of Rome’s dying Republic. Marcus is rugged, handsome, and owns abundant military talent, but upon entering manhood, he falls prey to the excesses of a violent society. His whoring, gambling, and drinking eventually reap dire consequences. Through a series of personal tragedies, Marcus must come into his own through blood, blades, and death. Once he finally earns a military commission, he faces an uphill battle to earn the respect and admiration of soldiers, proconsuls, and kings. Desperate to redeem his name and carve a legacy for himself, he refuses to let warring rebels, scheming politicians, or even an alluring young Egyptian princess stand in his way.

Author Brook Allen has a passion for ancient history—especially 1st century BC Rome. Her Antonius Trilogy is a detailed account of the life of Marcus Antonius—Marc Antony, which she worked on for fifteen years. The first instalment, Antonius: Son of Rome was published in March 2019. It follows Antony as a young man, from the age of eleven, when his father died in disgrace, until he’s twenty-seven and meets Cleopatra for the first time. Brook’s second book is Antonius: Second in Command, dealing with Antony’s tumultuous rise to power at Caesar’s side and culminating with the civil war against Brutus and Cassius. Antonius: Soldier of Fate is the last book in the trilogy, spotlighting the romance between Antonius and Cleopatra and the historic war with Octavian Caesar.

In researching the Antonius Trilogy, Brook’s travels have led her to Italy, Egypt, Greece, and even Turkey to explore places where Antony once lived, fought, and eventually died. While researching abroad, she consulted with scholars and archaeologists well-versed in Hellenistic and Roman history, specifically pinpointing the late Republican Period in Rome. Brook belongs to the Historical Novel Society and attends conferences as often as possible to study craft and meet fellow authors. In 2019, Son of Rome won the Coffee Pot Book Club Book of the Year Award. In 2020, it was honored with a silver medal in the international Reader’s Favorite Book Reviewers Book Awards and also won First Place in the prestigious Chaucer Division in the Chanticleer International Book Awards, 2020.

Brook is currently working on a new project spotlighting history from a little closer to home. Her upcoming work will take place in early 19th century Virginia and it’s been a delight to research her characters and their period throughout southwest Virginia and into Kentucky, Missouri, Montana, and Idaho.

Though she graduated from Asbury University with a B.A. in Music Education, Brook has always loved writing. She completed a Masters program at Hollins University with an emphasis in Ancient Roman studies, which helped prepare her for authoring her present works. Brook teaches full-time as a Music Educator and works in a rural public-school district near Roanoke, Virginia. Her personal interests include travel, cycling, hiking in the woods, reading, and spending downtime with her husband and big, black dog, Jak. She lives in the heart of southwest Virginia in the scenic Blue Ridge Mountains

Connect with Brook:

Website • Twitter • Facebook • Instagram

Goodreads • Amazon Author Page

No comments:

Post a Comment