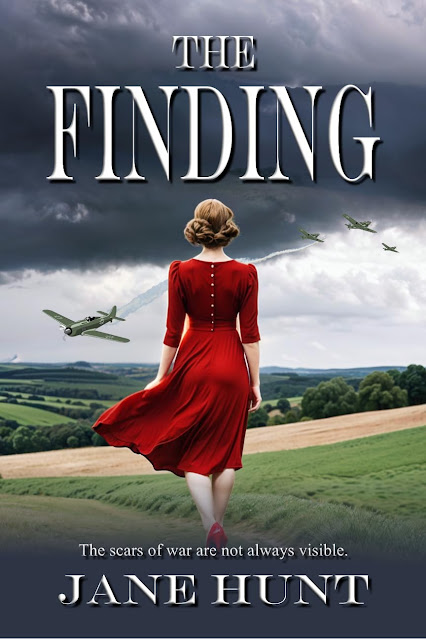

The Finding

This poignant novella is a tale of forbidden love, resilience, and the human cost of war.

In the quiet fields of Wiltshire during World War II, Eveline, a sheltered young woman, stumbles upon a life-altering discovery: a German Luftwaffe pilot, Fritz, has crash-landed near her home. Against the backdrop of war and suspicion, her family takes the injured man in, nursing him back to health. Beneath his reserved demeanor and burned body, Eveline senses a mystery—and something stirs an unfamiliar longing within her.

As Eveline’s infatuation deepens, she faces a storm of challenges: her overbearing mother’s rigid rules, a zealous preacher’s warnings, and the scrutiny of the town’s gossips. Despite Fritz’s attempts to keep her at arm’s length Eveline’s heart defies reason, falling for the man branded as her enemy.

But Fritz harbors secrets that could shatter Eveline’s fragile world. When the truths of war and the weight of loyalty collide, Eveline must confront the reality of loving someone forbidden.

Will their bond endure the hostility of a nation at war? Or will the scars of betrayal and loss prove impossible to heal?

Where to find Jane: