Godwine Kingmaker

The Last Great Saxon Earls

by Mercedes Rochelle

Publication Date: April 4th, 2015

Publisher: Sergeant Press

Pages: 351

Genre: Historical Fiction

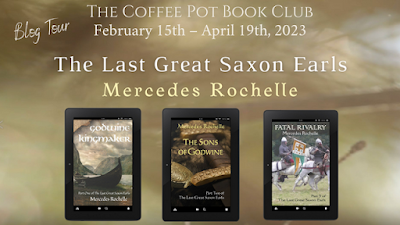

THE LAST GREAT SAXON EARLS:

GODWINE KINGMAKER

THE SONS OF GODWINE

FATAL RIVALRY

They showed so much promise. What happened to the Godwines? How did they lose their grip? Who was this Godwine anyway, first Earl of Wessex and known as the Kingmaker? Was he an unscrupulous schemer, using King and Witan to gain power? Or was he the greatest of all Saxon Earls, protector of the English against the hated Normans? The answer depends on who you ask.

He was befriended by the Danes, raised up by Canute the Great, given an Earldom and a wife from the highest Danish ranks. He sired nine children, among them four Earls, a Queen and a future King. Along with his power came a struggle to keep his enemies at bay, and Godwine's best efforts were brought down by the misdeeds of his eldest son Swegn.

Although he became father-in-law to a reluctant Edward the Confessor, his fortunes dwindled as the Normans gained prominence at court. Driven into exile, Godwine regathered his forces and came back even stronger, only to discover that his second son Harold was destined to surpass him in renown and glory.

Death of Edward the Confessor, Jan. 5 1066

We think of King Edward as an old man by 1066, and I suppose by 11th century standards, 63 years of age was getting on there. However, his health declined so precipitously the previous month that Duke William of Normandy was caught unawares, and by the time the Normans got the news, Harold was crowned as a fait accompli.

It was thought by many that Edward's sudden illness was caused by the revolt of the Northumbrians in October of 1065. This rebellion resulted in the enforced exile of his favorite, Tostig, and the King's realization that his commands were ineffectual.

Edward wanted to call up the fyrd and compel his rebellious subjects to capitulate and accept Tostig back. Alas, because of the lateness of the year and the general abhorrence for civil war, he couldn't gather enough support for this course of action. Even Harold was unwilling to cooperate, and Edward was obliged to accept the Northumbrians’ terms and acknowledge Morkere as their new Earl, even though their hastily called election was illegal. It was thought that Edward was so humiliated that he suffered a number of strokes as a result.

Whether or not this was the true cause of Edward’s decline, he was noticeably ill by Christmas Eve. He managed to stumble through the next couple of days but took to his bed on the 28th of December, unable to attend the consecration of his great Westminster Abbey. For the next week, he slipped in and out of unconsciousness, but rallied enough to give a long and drawn-out account of a dream he had, predicting the fall and misery of England. It was said that Archbishop Stigand whispered to Harold that this was the babbling of an old man worn out by sickness.

More to the point, the moment had come where Edward was to declare his heir. As with just about everything else, no one knows exactly what happened. If we take the Bayeux Tapestry literally, there were only four witnesses: Queen Editha, Harold, Archbishop Stigand, and Robert the Staller, Edward’s Norman friend who held the King in his arms. It is possible (and I think probable) that there were other witnesses. Nonetheless, the King was apparently conscious and alert by now, and he addressed the Queen, who he compared to a beloved daughter. Then, according to the Vita Aedwardi Regis, he stretched his hand to Harold and said, “I commend this woman and all the kingdom to your protection.” He exhorted Harold to care for her and any Normans who chose to stay, or give safe conduct to those who decided to leave. Perhaps wisely, he also commanded that they announce his death at once, so the people could pray for him. Did he fear that Harold would keep his death a secret so he could properly arrange for the succession?

Were his words really so ambiguous? It’s curious that the venerable Edward A. Freedom chose to interpret the statement as “To thee, Harold my brother, I commit my Kingdom” and justified his decision in a footnote. Edward could just as easily have been assigning the regency to Harold rather than the crown, but obviously Harold chose the latter. Interestingly enough, most contemporary documents—even those from Normandy—seem to accept that the King had declared Harold his heir.

It is possible that Harold brought the issue to the Witan that very night, since the following day saw both a funeral and a coronation at Westminster Abbey; I don’t see how there could have been time for a Witenagemot in between the two ceremonies. Without the Witan’s approval, Harold’s kingship would have been unlawful. King Edward’s wishes were secondary, and everybody knew it (except, perhaps, for Duke William). In times of trouble, the country needed a strong hand at the helm and Harold had proven himself a good administrator and a formidable warrior.

This series is available to read on #KindleUnlimited.

Mercedes Rochelle

Mercedes Rochelle is an ardent lover of medieval history, and has channeled this interest into fiction writing. She believes that good Historical Fiction, or Faction as it’s coming to be known, is an excellent way to introduce the subject to curious readers. She also writes a blog: HistoricalBritainBlog.com to explore the history behind the story.

Born in St. Louis, MO, she received by BA in Literature at the Univ. of Missouri St.Louis in 1979 then moved to New York in 1982 while in her mid-20s to “see the world”. The search hasn’t ended!

Today she lives in Sergeantsville, NJ with her husband in a log home they had built themselves.

Connect with Mercedes:

Thanks so much for hosting me!

ReplyDeleteMy pleasure, Mercedes. You're always welcome. xx

Delete